My Name is Joe Black (Part 1 of 2)

Note: This story contains some language and themes that may not be suitable for younger readers.

I

My name is Joe Black.

As luck or whatever else would have it, you could also call my skin black. It’s actually the color of coffee with two creams, but the language we use isn’t always good for picking up on subtleties.

An ancestor of mine probably had very dark skin, and that’s where my name came from. If that’s the case, then I suppose the name Black didn’t have anything to do with luck. Just humor, meanness, or simple observation. Maybe a combination of all three.

The ancestor in question might have been a blacksmith or perhaps even a practitioner of black magic. That last option sounds exciting enough for me to wish it were true, but it’s probably not true at all.

It was probably just skin color – nothing more and nothing less – that led to my family name of Black. So much of my life as I live it over and over again has been about skin color and nothing more.

That’s not true, or at least it’s not altogether true. So much of the life I’ve led over and over has everything to do with skin color, but those lives have also been about far more.

Now that I think of it, I’ve never looked into the name thing too deeply. I guess I’ve always just worn my name like the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball jersey I wore on the pitching mound, toeing the rubber, contemplating my next pitch.

Maybe that’s not so strange. I mean, I’ve never gone on a mission to find out who stitched the cloth of my jersey. Likewise, I never teased out who gave me the name Black, the name that, like the jersey, I wear time and time again.

Why haven’t I ever looked into the origin of my name before? You know, it’s never really even crossed my mind to do it. That is, it never crossed my before this moment, before I started this letter to you as I sit in my car and wait to die.

I guess I could plead busyness. I was simply too busy living the lives I’ve been given to live. I could say I was just too busy following the orders I’ve chosen to receive and to obey. But those excuses would be cop outs.

I guess I had other things on my mind each time I took a turn around the track of life, piling up hundreds of laps as I went. Still, it’s pathetic that I never bothered to hunt around, take a look, and find out where the name Black came from.

Now, future reader, if you don’t know where your name came from, that’s sad, and maybe a little lazy. But for me, it’s really inexcusable. That doesn’t make sense to you right now. I know that. But it will.

What’s the old cliché? You never find time; you only make it. Guess it’s true, even for me, someone who has had more years than there are stars visible in the night sky over red-hot Phoenix, my city. Most clichés are true, at least on some level.

But I should have done it. My name is beyond important to me. It has always been what I call “a solid” in my line of work. In other words, in each variation of my life, my name has been a reliable constant. Each time the baby me first cracked out of momma’s womb and opened his eyes for the first time, the surname Black was placed on his birth certificate.

Other details, little blips on the radar screen of history that are big things for me personally, varied so often and so randomly. It’s really a puzzle why my name didn’t ever come out different one time. I’ll chalk it up to divine humor.

More than once, I was born the next town over from the last life. Once or twice, I came out a left-hander. For some fool reason, in a dozen of my lifetimes I developed an allergy to milk.

Or consider this oddity: virtually every time around life’s bases I felt a strong connection to the Baptists. But then there was that one lifetime I craved from my very depths membership in the Episcopal Church with the all its incense and devotion to The Book of Common Prayer.

Weird, just weird.

But I shouldn’t expect any different. Who really knows the nooks and crannies of time, much less the intricacies of the mind of God? When you spend as much time as I have spent exploring both, I suppose it’s inevitable you’d find some weird shit in both.

Nonetheless, every time around the track the name “Black” was solid, dependable, and written on the paychecks signed by Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley and given to me as one of his faithful, hard-working pitchers.

The name Black causes me such obvious problems. If this hasn’t occurred to you, please put my letter down and just think about it for a blink or two. My name is Joe Black. I pitch for the Brooklyn Dodgers. My rookie season was 1952. I am black. Hint. Wink. Nudge. Get it? I knew you could.

In case you didn’t, I’ll spell it out for you. My name gives bigots in every version of our world an easy thing to shout at me when I have a little trouble finding the strike zone.

It’s a sin and a shame to shout insults at a person like me just trying get a batter to swing at a ball in the dirt. But, it’s a double sin to fling those insults at me without having to employ a minimum of creativity and wit. My last name simply does too much work for the narrow-minded, light-skinned men in the stands wearing their suits, ties, and superiority complexes.

I know I need to slow down for you. I am rambling all over the place and just trusting you to keep up. That expectation is completely absurd given what I need to tell you. What I need to tell you is something that you have no schema to anticipate, much less keep up with. And that’s especially the case if I, in a fit of subconscious cruelty, decide to start you off in the middle of things.

I refuse to do that. I have no desire to be cruel. I have seen and overcome too much cruelty to add more of its slime to creation, to the holy spiral of the worlds.

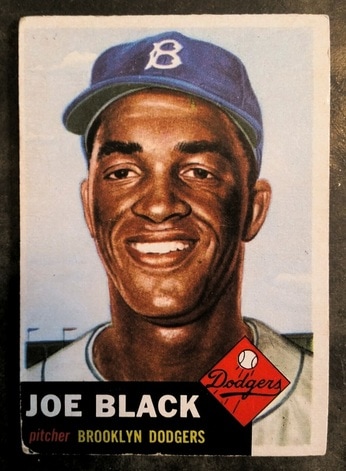

So, first off, I will tell you things easily understood. These are things that you could read off the back of one of my baseball cards. They’re stats, but obviously not stats about me as I am now. Right now I am an old man sitting in a burgundy-colored Buick sedan scribbling notes and waiting to die (which, believe me, is not as dramatic for me as it sounds to you).

The snippets of information that follow in the next couple of paragraphs are about a much younger man who was me. And, with the slight alteration of a detail here or there, they are details about a young man I will be twice more.

My name is Joe Black. I was, am, and will be a pitcher for the Brooklyn Dodgers. My birthdate is February 8th, 1924. I am almost always born in Plainfield, New Jersey, although I have also been born in the neighboring towns of Elizabeth and Bridgewater.

No matter which version of my life I live, I am a big man standing six foot two and weighing two hundred and fifteen pounds. Across the expanse of my lives, as an adult I’ve never been shorter than 6’ 1” and lighter than two hundred pounds. Thankfully, I’ve also never been tubby around the middle. I couldn’t stomach that. (Pun intended, but laughter not expected.)

I was named to the Major League Baseball Rookie All-Star Team in 1952. That same season I was named by my manager, Chuck Dressen, the Dodger’s team MVP. In the ’52 season I pitched more complete games than anyone else in the National League. I started game three of the 1952 World Series. I joined the Dodgers after only one year in the minor leagues. I have a bright smile and a melancholy heart.

I became a Dodger six years after Jackie Robinson did.

There’s a name I’m sure you know. You know Jackie’s name, even if you don’t know mine. And you know what it meant for the social and spiritual history of the United States of America for Jack to play baseball for the Dodgers when he did.

You know his name instead of mine because you and I are from the same version of the world. You and I are both from what people in my line of work call V1, which simply means “Version One”. Ours is the world through which God will eventually spawn 359 more. After that, who really knows what will happen except, in the grandiose, Bible-sounding, but unsatisfying way it has always been put to me, “everything will be complete.”

In V1, in our world, I can just forget all about measuring up to Jackie. Heck, I’m not even as well-known as other black teammates of mine like Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella (whose daddy was actually Italian, but I’m not one to quibble).

But here’s the joke I’m letting you in on. That’s the way it is in V1. However, in all the other versions of the world, no one remembers Jackie Robinson. Instead the school children all learn the name Joe Black.

The rest of what I have to tell you can’t fit on the back of all the bubblegum cards in the world.

II

After I retired from the Dodgers, I was not at all set for life as far as finances were concerned. It had nothing to do with gold watches, hookers, or dubious investment opportunities pitched to me by distant cousins. It’s just that back then wasn’t the same as today. In the 50s there wasn’t enough money in baseball with which to make many big money decisions of any kind – good, bad, or indifferent.

As a former player from that old era still living in the 2000s, I’d be lying if I didn’t fess up to being a bit bummed out about that. But as more than a ballplayer, as a person, I suppose deep-down I’m fine with it.

Still needing income opened parts of life to me that wouldn’t have been unlocked had I retired and spent the next series of decades playing the part of some black, fat, diamond-encrusted Elvis.

(I have to pause here for a flight of imagination concerning me as a rich retired modern player. Picture me sitting on a leather couch made from the slaughter of a thousand unblemished sacred bulls. Picture me watching a 200 inch TV and eating ice cream out of a platinum bowl. Picture me spinning a revolver of pure gold on the index finger of the hand not holding the spoon for my ice cream. And, oh yeah, the spoon would have been fashioned from the tusk of a poached elephant stolen from the most endangered of breeds. Good Lord, no!)

All of this is an overwrought way of saying I was not rich when I retired from baseball. And that was fine with me.

So, after pro ball, I taught junior high school. Eventually, I retired to the desert, to Arizona, to Scottsdale in particular. Scottsdale sits on the east side of the Phoenix metro area. I went there to age and die simply because I’ve always hated humidity and I still loved baseball.

You see, half of the major league baseball teams do their spring training in the Phoenix area. It’s called the Cactus League. For instance, Scottsdale has the San Francisco Giants. Back when I was playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers I knew the Giants as a bitter, cross-town, New York rival. But then the Giants, like my Dodgers, moved out to California, and they mellowed.

For my part, I’ve mellowed even more than the teams. I’ve also been blessed. Although baseball did not bring me wealth, age has brought me an ease of spirit and a lack of bitterness about the past. With my easy spirit I’ve become a bit of a fixture in the Phoenix-area baseball culture. I even fell in love with the local team, the Diamondbacks, who’d done me a favor and increased my ease by rising up and beating the Yankees in a World Series.

During each spring training season, I’d drop into the different stadiums and the teams’ media departments would trot me out like some sort of holy relic. We’d chat about days the days of Jackie and me and a hundred other dark men swinging bats under the glare of white faces. We’d chat about a time that seemed in many ways as far back as the days of Jesus walking the Galilean seashore multiplying loaves and fish.

I’d tell the cameras and microphones about how I remembered looking up into the stands from the pitching mound and seeing a sea of felt fedoras casting shadows on peach-colored people. I’d tell about how those people’s heads were often covered, but their prejudices exposed. I’d chuckle about the unhelpfulness of my last name. I’d talk about Jackie. I’d talk about doing what he was doing by his side and by the side of many other men even less known than me. They’d nod seriously, celebrate “how far things had come,” and then I’d go home.

One afternoon I dropped in on a Giants game in Scottsdale. After my “I Was There” historical moment in the broadcast booth, I checked my watch. It was about three in the afternoon, so I wandered a few blocks into Old Town Scottsdale to scare up a late lunch (or was it early dinner?) at The Pink Pony. It’s a stupid name for a restaurant, but it’s a local institution, and it’s a regular place for me to slip out of the heat and get a steak.

All this sounds rustic and quaint, but it very much isn’t. Modern Scottsdale is a curious place. Its Wild West roots are just a veneer now, a hollow show played up to sell Kachina dolls and paintings with Marlboro Men riding horses into sunsets. Old Town Scottsdale is lined with bars and art galleries and a glitzed out shopping mall that have red Ferraris in the parking lot.

But I like it. I like the displaced, almost schizophrenic sense it has. I like how Scottsdale, as nice as it is and as important as it seems to be, still doesn’t seem to fit together quite right in the world. I like it because that’s the way I’ve felt for thousands of years about myself.

Scottsdale is half old people like me who fled the East or the Midwest and brought with us our grass yards, strange ways of pronouncing vowels, and devotion to sports teams that make no sense out here – teams like the Green Bay Packers. Most of these folk are white, but otherwise they’re pretty much like me, especially when it comes to being old.

That’s one half of schizo Scottsdale. The other half is Beverly Hills East. It’s nightlife and young people rolling in high-dollar cars pretending they’re partners in law firms when all they actually do is wait tables for three bucks an hour plus tips. This sexy Scottsdale is where NBA legend Charles Barkley got busted one year for receiving oral in a moving automobile. This Scottsdale is sun-darkened skin stretched tight by surgical augmentation.

Anyway, during the afternoon in question, I was half done with my steak at The Pink Pony. At that point in the meal a man entered the restaurant and moved directly to my table. He was very tall, very tan, very bald – hairless as a cue ball, in fact. But he also looked very young.

This happens from time to time to me, even back in V1 where I was almost unknown. Sometimes baseball fans who’ve seen me do my thing on the TV can’t resist coming up to me when I enter their actual physical space. Other times a geezer saddles up to me because he still remembers me from back when I used to lace them up, pitch the ball, and bear the slings and arrows of infamy.

I usually am pleasant but brief with the folks who come to my table and invade my meals. But this guy made me take notice. He was in a Brooklyn Dodgers cap and jersey and, honestly, they looked legit – not replicas but game-worn real mccoys. Yet, at the same time, they looked fresh. It didn’t make any sense. I must have gawked. He must have seen me gawking.

“I’m a big fan,” he said.

“Of who?” I said.

“Of you. Of Joe Black. Of course.” He spun around to give me a 360 degree look at the jersey. And, goddamn. It was one of mine.

“How you get that?” I said.

“I’ve got connections,” he said.

“Obviously,” I said.

“Obviously,” he said.

“So you’re a fan of mine. You’re a fan of the ball I pitched back when dinosaurs roamed the earth and the Israelite slaves were crossing the split sea.”

He laughed politely. “Well, it wasn’t that long ago, Joe. But plenty long ago nonetheless.”

“You look too young for that,” I said.

“Looks can be deceiving,” he said.

“So you’re a fan of me for my stats with the Dodgers. Is that so?”

“Stats and more.”

This time I was the one who laughed. And I decided to play it coy. “What?” I said. “You also love me for my time teaching junior high school.”

“Joe, to be straight with you, I’m a fan of how you have been black, negro, dark, whatever you want to call it. I am especially a fan of how you handled who you are in the major leagues. How you did this is more important than you know, Joe.”

That wasn’t the first time someone had said something like that to me. It wasn’t even the first time a white guy had said something like that. I take it as a compliment, but it still sounds funny and usually catches me short for a moment. It catches me as ignorant and insulting coming from a white guy’s lips. But what he said next was a first for me.

“Joe, do you remember writing these words?”

“What words?”

“These words: ‘I am writing you, not as a baseball player, but as one human being to another. I cannot help, nor possibly alter, what you think about me. I speak to you only as an American who happens to be an American Negro and proud of my heritage. We ask for nothing special. We ask only in sports that we be permitted to compete on an even basis. Certainly you, and the people of Louisiana, are capable of facing that competition. I wish you could see this as I do, but I hold little hope. I wish you could comprehend how unfair it is for the accident of birth to make such a difference to you. I am happy for you, that you were born white. Things would have been extremely difficult for you otherwise.”

I heaved emotionally. The tan, bald man performed my words like an actor on the stage offering a speech from Hamlet. He hit all the right notes of intonation and stress. It had been decades since I had written the words, but as he said them, it was like I was writing them again for the first time. I was overcome. It took all I had to stammer out a reply.

“Yes, yes, yes. I remember those words. I wrote them in a letter to a loud-mouthed white man, a sportswriter from Louisiana. The dude wanted interracial sports to be a crime in Louisiana. But, sir, you’re certainly not that man. And you’re not likely his grandson either. How the hell do you know my words like an actor doing some damn monologue?”

It was during my response to his performance of my private correspondence that the bald man sat down next to me, took out an old looking baseball, and placed it in front of me right between my plate of steak and my Diet Coke.

The ball was ancient looking, scuffed from banging against infield dirt and outfield grass. It was covered with squiggles from a blue ballpoint pen, the autographs of baseball players.

The autograph that jumped out at me was Jackie Robinson’s. It was all neat diagonal letters reflecting the careful control of the man who wrote them. I picked it up and spun it in my hand as I looked for my name. There it was. Joe Black.

“Yep. That’s your autograph, Joe,” the bald man said. “The ball is from your rookie season. It’s one of the balls from your pitching debut on the mound with the Dodgers. I want you to keep it.”

“Bullshit,” I said.

“True shit,” he said.

“Thanks,” I said.

“Joe, what you have done matters more than even you think it does. And, it needs to be done again and again if all is to come out right in the end. Come out right everywhere and in every way. What you did takes a steady hand and a durable heart. And, well, Jackie opted out, Joe.”

Still holding the ball, I looked at him. He stood up.

“What are you talking about?” I said.

“Joe, if you want to know more take the ball into a large, darkened room, and work it over. Rub it up like you would a fresh ball before you’d be ready to pitch it. The ball is more than it seems. So much is more than it seems. You are more than you seem, Joe. Or, rather, you can be, if you are willing to sign up.”

He started for the front door of the restaurant.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Martin,” he said. Then he started walking to the exit.

Crazy, fucking fool. That was the verdict I handed down silently in my head.

At that moment, he stopped, looked back at me, grinned wide and long, and called out, “Indeed I am, Joe. Indeed I am.” Then he opened the door, the desert sun erupted around him, and he stepped into the day, his form completely encircled in light.

My name is Joe Black.

As luck or whatever else would have it, you could also call my skin black. It’s actually the color of coffee with two creams, but the language we use isn’t always good for picking up on subtleties.

An ancestor of mine probably had very dark skin, and that’s where my name came from. If that’s the case, then I suppose the name Black didn’t have anything to do with luck. Just humor, meanness, or simple observation. Maybe a combination of all three.

The ancestor in question might have been a blacksmith or perhaps even a practitioner of black magic. That last option sounds exciting enough for me to wish it were true, but it’s probably not true at all.

It was probably just skin color – nothing more and nothing less – that led to my family name of Black. So much of my life as I live it over and over again has been about skin color and nothing more.

That’s not true, or at least it’s not altogether true. So much of the life I’ve led over and over has everything to do with skin color, but those lives have also been about far more.

Now that I think of it, I’ve never looked into the name thing too deeply. I guess I’ve always just worn my name like the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball jersey I wore on the pitching mound, toeing the rubber, contemplating my next pitch.

Maybe that’s not so strange. I mean, I’ve never gone on a mission to find out who stitched the cloth of my jersey. Likewise, I never teased out who gave me the name Black, the name that, like the jersey, I wear time and time again.

Why haven’t I ever looked into the origin of my name before? You know, it’s never really even crossed my mind to do it. That is, it never crossed my before this moment, before I started this letter to you as I sit in my car and wait to die.

I guess I could plead busyness. I was simply too busy living the lives I’ve been given to live. I could say I was just too busy following the orders I’ve chosen to receive and to obey. But those excuses would be cop outs.

I guess I had other things on my mind each time I took a turn around the track of life, piling up hundreds of laps as I went. Still, it’s pathetic that I never bothered to hunt around, take a look, and find out where the name Black came from.

Now, future reader, if you don’t know where your name came from, that’s sad, and maybe a little lazy. But for me, it’s really inexcusable. That doesn’t make sense to you right now. I know that. But it will.

What’s the old cliché? You never find time; you only make it. Guess it’s true, even for me, someone who has had more years than there are stars visible in the night sky over red-hot Phoenix, my city. Most clichés are true, at least on some level.

But I should have done it. My name is beyond important to me. It has always been what I call “a solid” in my line of work. In other words, in each variation of my life, my name has been a reliable constant. Each time the baby me first cracked out of momma’s womb and opened his eyes for the first time, the surname Black was placed on his birth certificate.

Other details, little blips on the radar screen of history that are big things for me personally, varied so often and so randomly. It’s really a puzzle why my name didn’t ever come out different one time. I’ll chalk it up to divine humor.

More than once, I was born the next town over from the last life. Once or twice, I came out a left-hander. For some fool reason, in a dozen of my lifetimes I developed an allergy to milk.

Or consider this oddity: virtually every time around life’s bases I felt a strong connection to the Baptists. But then there was that one lifetime I craved from my very depths membership in the Episcopal Church with the all its incense and devotion to The Book of Common Prayer.

Weird, just weird.

But I shouldn’t expect any different. Who really knows the nooks and crannies of time, much less the intricacies of the mind of God? When you spend as much time as I have spent exploring both, I suppose it’s inevitable you’d find some weird shit in both.

Nonetheless, every time around the track the name “Black” was solid, dependable, and written on the paychecks signed by Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley and given to me as one of his faithful, hard-working pitchers.

The name Black causes me such obvious problems. If this hasn’t occurred to you, please put my letter down and just think about it for a blink or two. My name is Joe Black. I pitch for the Brooklyn Dodgers. My rookie season was 1952. I am black. Hint. Wink. Nudge. Get it? I knew you could.

In case you didn’t, I’ll spell it out for you. My name gives bigots in every version of our world an easy thing to shout at me when I have a little trouble finding the strike zone.

It’s a sin and a shame to shout insults at a person like me just trying get a batter to swing at a ball in the dirt. But, it’s a double sin to fling those insults at me without having to employ a minimum of creativity and wit. My last name simply does too much work for the narrow-minded, light-skinned men in the stands wearing their suits, ties, and superiority complexes.

I know I need to slow down for you. I am rambling all over the place and just trusting you to keep up. That expectation is completely absurd given what I need to tell you. What I need to tell you is something that you have no schema to anticipate, much less keep up with. And that’s especially the case if I, in a fit of subconscious cruelty, decide to start you off in the middle of things.

I refuse to do that. I have no desire to be cruel. I have seen and overcome too much cruelty to add more of its slime to creation, to the holy spiral of the worlds.

So, first off, I will tell you things easily understood. These are things that you could read off the back of one of my baseball cards. They’re stats, but obviously not stats about me as I am now. Right now I am an old man sitting in a burgundy-colored Buick sedan scribbling notes and waiting to die (which, believe me, is not as dramatic for me as it sounds to you).

The snippets of information that follow in the next couple of paragraphs are about a much younger man who was me. And, with the slight alteration of a detail here or there, they are details about a young man I will be twice more.

My name is Joe Black. I was, am, and will be a pitcher for the Brooklyn Dodgers. My birthdate is February 8th, 1924. I am almost always born in Plainfield, New Jersey, although I have also been born in the neighboring towns of Elizabeth and Bridgewater.

No matter which version of my life I live, I am a big man standing six foot two and weighing two hundred and fifteen pounds. Across the expanse of my lives, as an adult I’ve never been shorter than 6’ 1” and lighter than two hundred pounds. Thankfully, I’ve also never been tubby around the middle. I couldn’t stomach that. (Pun intended, but laughter not expected.)

I was named to the Major League Baseball Rookie All-Star Team in 1952. That same season I was named by my manager, Chuck Dressen, the Dodger’s team MVP. In the ’52 season I pitched more complete games than anyone else in the National League. I started game three of the 1952 World Series. I joined the Dodgers after only one year in the minor leagues. I have a bright smile and a melancholy heart.

I became a Dodger six years after Jackie Robinson did.

There’s a name I’m sure you know. You know Jackie’s name, even if you don’t know mine. And you know what it meant for the social and spiritual history of the United States of America for Jack to play baseball for the Dodgers when he did.

You know his name instead of mine because you and I are from the same version of the world. You and I are both from what people in my line of work call V1, which simply means “Version One”. Ours is the world through which God will eventually spawn 359 more. After that, who really knows what will happen except, in the grandiose, Bible-sounding, but unsatisfying way it has always been put to me, “everything will be complete.”

In V1, in our world, I can just forget all about measuring up to Jackie. Heck, I’m not even as well-known as other black teammates of mine like Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella (whose daddy was actually Italian, but I’m not one to quibble).

But here’s the joke I’m letting you in on. That’s the way it is in V1. However, in all the other versions of the world, no one remembers Jackie Robinson. Instead the school children all learn the name Joe Black.

The rest of what I have to tell you can’t fit on the back of all the bubblegum cards in the world.

II

After I retired from the Dodgers, I was not at all set for life as far as finances were concerned. It had nothing to do with gold watches, hookers, or dubious investment opportunities pitched to me by distant cousins. It’s just that back then wasn’t the same as today. In the 50s there wasn’t enough money in baseball with which to make many big money decisions of any kind – good, bad, or indifferent.

As a former player from that old era still living in the 2000s, I’d be lying if I didn’t fess up to being a bit bummed out about that. But as more than a ballplayer, as a person, I suppose deep-down I’m fine with it.

Still needing income opened parts of life to me that wouldn’t have been unlocked had I retired and spent the next series of decades playing the part of some black, fat, diamond-encrusted Elvis.

(I have to pause here for a flight of imagination concerning me as a rich retired modern player. Picture me sitting on a leather couch made from the slaughter of a thousand unblemished sacred bulls. Picture me watching a 200 inch TV and eating ice cream out of a platinum bowl. Picture me spinning a revolver of pure gold on the index finger of the hand not holding the spoon for my ice cream. And, oh yeah, the spoon would have been fashioned from the tusk of a poached elephant stolen from the most endangered of breeds. Good Lord, no!)

All of this is an overwrought way of saying I was not rich when I retired from baseball. And that was fine with me.

So, after pro ball, I taught junior high school. Eventually, I retired to the desert, to Arizona, to Scottsdale in particular. Scottsdale sits on the east side of the Phoenix metro area. I went there to age and die simply because I’ve always hated humidity and I still loved baseball.

You see, half of the major league baseball teams do their spring training in the Phoenix area. It’s called the Cactus League. For instance, Scottsdale has the San Francisco Giants. Back when I was playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers I knew the Giants as a bitter, cross-town, New York rival. But then the Giants, like my Dodgers, moved out to California, and they mellowed.

For my part, I’ve mellowed even more than the teams. I’ve also been blessed. Although baseball did not bring me wealth, age has brought me an ease of spirit and a lack of bitterness about the past. With my easy spirit I’ve become a bit of a fixture in the Phoenix-area baseball culture. I even fell in love with the local team, the Diamondbacks, who’d done me a favor and increased my ease by rising up and beating the Yankees in a World Series.

During each spring training season, I’d drop into the different stadiums and the teams’ media departments would trot me out like some sort of holy relic. We’d chat about days the days of Jackie and me and a hundred other dark men swinging bats under the glare of white faces. We’d chat about a time that seemed in many ways as far back as the days of Jesus walking the Galilean seashore multiplying loaves and fish.

I’d tell the cameras and microphones about how I remembered looking up into the stands from the pitching mound and seeing a sea of felt fedoras casting shadows on peach-colored people. I’d tell about how those people’s heads were often covered, but their prejudices exposed. I’d chuckle about the unhelpfulness of my last name. I’d talk about Jackie. I’d talk about doing what he was doing by his side and by the side of many other men even less known than me. They’d nod seriously, celebrate “how far things had come,” and then I’d go home.

One afternoon I dropped in on a Giants game in Scottsdale. After my “I Was There” historical moment in the broadcast booth, I checked my watch. It was about three in the afternoon, so I wandered a few blocks into Old Town Scottsdale to scare up a late lunch (or was it early dinner?) at The Pink Pony. It’s a stupid name for a restaurant, but it’s a local institution, and it’s a regular place for me to slip out of the heat and get a steak.

All this sounds rustic and quaint, but it very much isn’t. Modern Scottsdale is a curious place. Its Wild West roots are just a veneer now, a hollow show played up to sell Kachina dolls and paintings with Marlboro Men riding horses into sunsets. Old Town Scottsdale is lined with bars and art galleries and a glitzed out shopping mall that have red Ferraris in the parking lot.

But I like it. I like the displaced, almost schizophrenic sense it has. I like how Scottsdale, as nice as it is and as important as it seems to be, still doesn’t seem to fit together quite right in the world. I like it because that’s the way I’ve felt for thousands of years about myself.

Scottsdale is half old people like me who fled the East or the Midwest and brought with us our grass yards, strange ways of pronouncing vowels, and devotion to sports teams that make no sense out here – teams like the Green Bay Packers. Most of these folk are white, but otherwise they’re pretty much like me, especially when it comes to being old.

That’s one half of schizo Scottsdale. The other half is Beverly Hills East. It’s nightlife and young people rolling in high-dollar cars pretending they’re partners in law firms when all they actually do is wait tables for three bucks an hour plus tips. This sexy Scottsdale is where NBA legend Charles Barkley got busted one year for receiving oral in a moving automobile. This Scottsdale is sun-darkened skin stretched tight by surgical augmentation.

Anyway, during the afternoon in question, I was half done with my steak at The Pink Pony. At that point in the meal a man entered the restaurant and moved directly to my table. He was very tall, very tan, very bald – hairless as a cue ball, in fact. But he also looked very young.

This happens from time to time to me, even back in V1 where I was almost unknown. Sometimes baseball fans who’ve seen me do my thing on the TV can’t resist coming up to me when I enter their actual physical space. Other times a geezer saddles up to me because he still remembers me from back when I used to lace them up, pitch the ball, and bear the slings and arrows of infamy.

I usually am pleasant but brief with the folks who come to my table and invade my meals. But this guy made me take notice. He was in a Brooklyn Dodgers cap and jersey and, honestly, they looked legit – not replicas but game-worn real mccoys. Yet, at the same time, they looked fresh. It didn’t make any sense. I must have gawked. He must have seen me gawking.

“I’m a big fan,” he said.

“Of who?” I said.

“Of you. Of Joe Black. Of course.” He spun around to give me a 360 degree look at the jersey. And, goddamn. It was one of mine.

“How you get that?” I said.

“I’ve got connections,” he said.

“Obviously,” I said.

“Obviously,” he said.

“So you’re a fan of mine. You’re a fan of the ball I pitched back when dinosaurs roamed the earth and the Israelite slaves were crossing the split sea.”

He laughed politely. “Well, it wasn’t that long ago, Joe. But plenty long ago nonetheless.”

“You look too young for that,” I said.

“Looks can be deceiving,” he said.

“So you’re a fan of me for my stats with the Dodgers. Is that so?”

“Stats and more.”

This time I was the one who laughed. And I decided to play it coy. “What?” I said. “You also love me for my time teaching junior high school.”

“Joe, to be straight with you, I’m a fan of how you have been black, negro, dark, whatever you want to call it. I am especially a fan of how you handled who you are in the major leagues. How you did this is more important than you know, Joe.”

That wasn’t the first time someone had said something like that to me. It wasn’t even the first time a white guy had said something like that. I take it as a compliment, but it still sounds funny and usually catches me short for a moment. It catches me as ignorant and insulting coming from a white guy’s lips. But what he said next was a first for me.

“Joe, do you remember writing these words?”

“What words?”

“These words: ‘I am writing you, not as a baseball player, but as one human being to another. I cannot help, nor possibly alter, what you think about me. I speak to you only as an American who happens to be an American Negro and proud of my heritage. We ask for nothing special. We ask only in sports that we be permitted to compete on an even basis. Certainly you, and the people of Louisiana, are capable of facing that competition. I wish you could see this as I do, but I hold little hope. I wish you could comprehend how unfair it is for the accident of birth to make such a difference to you. I am happy for you, that you were born white. Things would have been extremely difficult for you otherwise.”

I heaved emotionally. The tan, bald man performed my words like an actor on the stage offering a speech from Hamlet. He hit all the right notes of intonation and stress. It had been decades since I had written the words, but as he said them, it was like I was writing them again for the first time. I was overcome. It took all I had to stammer out a reply.

“Yes, yes, yes. I remember those words. I wrote them in a letter to a loud-mouthed white man, a sportswriter from Louisiana. The dude wanted interracial sports to be a crime in Louisiana. But, sir, you’re certainly not that man. And you’re not likely his grandson either. How the hell do you know my words like an actor doing some damn monologue?”

It was during my response to his performance of my private correspondence that the bald man sat down next to me, took out an old looking baseball, and placed it in front of me right between my plate of steak and my Diet Coke.

The ball was ancient looking, scuffed from banging against infield dirt and outfield grass. It was covered with squiggles from a blue ballpoint pen, the autographs of baseball players.

The autograph that jumped out at me was Jackie Robinson’s. It was all neat diagonal letters reflecting the careful control of the man who wrote them. I picked it up and spun it in my hand as I looked for my name. There it was. Joe Black.

“Yep. That’s your autograph, Joe,” the bald man said. “The ball is from your rookie season. It’s one of the balls from your pitching debut on the mound with the Dodgers. I want you to keep it.”

“Bullshit,” I said.

“True shit,” he said.

“Thanks,” I said.

“Joe, what you have done matters more than even you think it does. And, it needs to be done again and again if all is to come out right in the end. Come out right everywhere and in every way. What you did takes a steady hand and a durable heart. And, well, Jackie opted out, Joe.”

Still holding the ball, I looked at him. He stood up.

“What are you talking about?” I said.

“Joe, if you want to know more take the ball into a large, darkened room, and work it over. Rub it up like you would a fresh ball before you’d be ready to pitch it. The ball is more than it seems. So much is more than it seems. You are more than you seem, Joe. Or, rather, you can be, if you are willing to sign up.”

He started for the front door of the restaurant.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Martin,” he said. Then he started walking to the exit.

Crazy, fucking fool. That was the verdict I handed down silently in my head.

At that moment, he stopped, looked back at me, grinned wide and long, and called out, “Indeed I am, Joe. Indeed I am.” Then he opened the door, the desert sun erupted around him, and he stepped into the day, his form completely encircled in light.